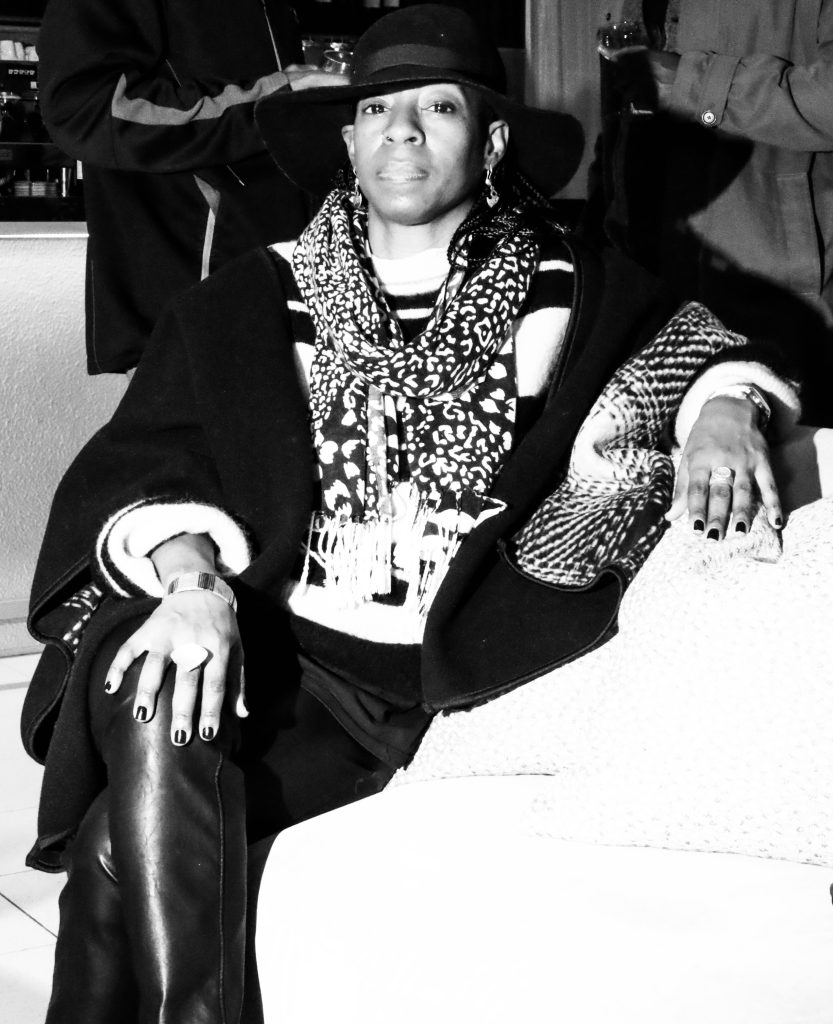

Àdéjọ́ke Àdéronke Túgbíyélé is a Nigerian American multidisciplinary visual artist and activist whose practice explores queer Yoruba aesthetics, challenges homophobia and stands in solidarity with the notion that “Queer Love is Not UnAfrican!” She is the first, openly queer woman of Nigerian descent to appear on CNN International in a 2014 interview with correspondent Vladimir Duthiers at Victoria Island, Lagos. In this interview, Àdéjọ́ke sits with Oludàmólá Ádébowálé of ASIRI Magazine to discuss how the Yoruba culture influences her work and dispels the widespread notion that queerness is foreign to the Yoruba culture.

Oludàmólá: How does your Yoruba heritage influence your artistic vision and the themes you choose to explore in your work?

Àdéjọ́ke: My Yoruba heritage is engrained from various influences including my upbringing, my experience living and working in Nigeria, the mentorship and friendship of other Yoruba artists and creatives – including architects, as well as through exposure to both classical and contemporary Yoruba aesthetics via publications, museum collections, galleries and more.

Oludàmólá: Can you elaborate on how indigenous Yoruba culture has historically accepted and created a fluid space for those who are queer or different?

Àdéjọ́ke: The European colonial encounter in Nigeria and Africa at large instilled certain beliefs about identity and personhood into Yoruba culture that had not existed prior. Yoruba language, in particular, is embedded with numerous references that underscore the fluidity, openness, tolerance, acceptance and even celebration of ‘difference.’ For example, gendered openness can be found in the naming of children, in the indigenous recognition of the intrinsic powers of over 200 deities, and within traditional performances such as Gélédé where men ‘cross-dress’ as women to honor ‘awon iya wa’ – our Mothers/Elders/Female Ancestors. In queer circles, this is known as a drag performance. Last but not least, fluidity can be found within important Yoruba principles such as Iwa L’ewa – the notion that beauty stems forth from the essential nature (character) of all human beings, regardless of identity – including queer beings.

Oludàmólá: Yoruba culture is deeply intertwined with nature and spirituality. How do these elements manifest in your art?

Àdéjọ́ke: The primary materials I work with stem from nature. Palm spines within my sculptures are repurposed traditional African brooms which originate from palm trees. Several works also employ wood, a medium that comes from trees and can be traced back to a plethora of indigenous Yoruba sculptures ranging from intricately carved wooden palace posts to royal stools, as well as numerous performance masks worn during Égúngún performances. The sacred and spiritual nature of all Yoruba aesthetics aligns with nature. I draw inspiration from this legacy in my practice, as I further innovate and create a new contemporary visual language.

Oludàmólá: Your work bridges the worlds of art and architecture. Can you describe how you integrate these two disciplines in your practice?

Àdéjọ́ke: Yes. Prior to art making I studied and trained in the field of architecture for two decades, beginning from age 14. It has been wonderful to return to architecture in recent years, exploring ways to bridge the two disciplines while also grounding the work in Yoruba aesthetics. One example is the project Visible/Invisible produced at Harvard Graduate School of Design in July 2022 – Design Discovery program.

The Visible/Invisible project involved forming an architectural structure out of the double-link, historically known as Solomon’s Knot, an aesthetic symbol known within Yoruba cosmology to signify royalty –. This symbol traditionally appeared on traditional attire, sculpture, currency and other objects, and continues to be used in contemporary times. The wrapping of traditional African brooms to form a ‘double helix’ along each bundled spine is a sacred process I have explored in numerous figurative sculptures produced over the past decade. For the first time, I brought this process into the realm of architecture with the Visible/Invisible project.

Medium: Palm spines; pastel; metallic silver spray paint; Dutch wax textile

Size: 20.5 x 36 inches (50.8 x 91.4 cm)

Oludàmólá: How do you address and represent queer identities within the context of Yoruba culture in your art?

Àdéjọ́ke: An important work from the year 2014, entitled Gélé Pride Flag (Collection of The Brooklyn Museum), transforms a material worn by Yoruba women in Nigeria into a statement about queer liberation in the form of the LGBTQ Pride Flag. I have similarly ‘queered the cloths’ of Dutch wax textiles and Àdìrẹ /indigo-dye in works such as the 2014 video/performance ‘AfroOdyssey IV: 100 Years Later ‘which I am humbled to share has been screened and exhibited globally. There are numerous works and references to queer concerns across a range of mediums in my practice including mixed-media works like Light-Beam (2017) and Determination (2017), as well as with my sculptures. For example, the installation entitled The Road to Divinity (2021) is made of palm spines and indigo paint – a nod to Yoruba Àdìrẹ.

Sex “Demons” is also an important work that queers two materials simultaneously – batik and Dutch wax textile. This mixed media work foreshadows some gestures currently appearing in my sculptures. But I don’t present the new figures in my sculptures as “demons,” at all, which was a sarcastic title to begin with anyway. Instead, they are enlightened spiritual entities whose spirituality and sexuality are completely aligned – in mind, body and spirit.

Oludàmólá: In what ways do you think your work challenges or complements contemporary discussions about gender and sexuality?

Àdéjọ́ke: My practice explores queer Yoruba aesthetics, challenges homophobia and stands in solidarity with the notion that “Queer Love is Not UnAfrican!” My work reveals how Yoruba philosophy embodies parallel conceptual frameworks that exist within Taoist, Buddhist and Hindu thought. Through the concept of ‘Visible/Invisible,’ I engage multiple dualities while simultaneously exploring ideas of flight, transformation and transcendence. My practice weaves both art and architecture and reveals clear links between classical Yoruba and Ancient Nubian aesthetics.

Medium: Batik on dutch-wax textile, on white cotton

Size: 36 x 72 inches (91.4 x 183 cm)

*Produced as Artist-In-Residence at the Guest House of Mr. Oliver Enwonwu, Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi, Nigeria.

Oludàmólá: Are there specific Yoruba symbols or motifs that you frequently incorporate into your work? What do they represent?

Àdéjọ́ke: Yes, I explore the sacred geometric markings found on Yoruba Àdìrẹ textiles through drawings, mixed media works and architecture. With the drawings in sacred geometry, I give a nod and pay honor to the long legacy of Àdìrẹ aesthetics pioneered by Chief Nike Davis Okundaye, Aina Allyson Davis and Peju Layiwola. I extend this into architecture through works-in-progress such as Kind Love: Remembrance (2024). A new gem in my library is The Cosmos in Stone: Sacred Geometry of a Master Mason, a book by Tom Bree. In it, Bree eloquently states, “The practice of sacred geometry is an external physical gesture whereby the artist ‘contemplatively’ seeks to encourage and effect an inward transformation of the soul.”

I have also explored the double link called Solomon’s Knot, mentioned earlier, with the project Visible/Invisible (2022). Within this project, circulation ultimately becomes a physical and visual journey through the double helix, as it ensures the body’s external movement in the environment mirrors internal circulation flow/patterns (DNA) within the human body itself. The ‘double helix’ – a reoccurring presence in my body of work – is part of a larger exploration into various sacred geometric forms including markings found on Yoruba Àdìrẹ indigo-dye textiles, as I examine elements of rhythm, repetition, order, mirroring and reflection.

In my design, the symbol is both extruded and dissected in such a way that alternating paths which ramp up and down in section and elevation, immediately draw one’s mind to renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic design of the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Meanwhile, my design simultaneously retains within the plan and the ‘parti’ the original form recognizable as Solomon’s Knot.

The foregoing describes my attempt to insert into the Western canon a long-ignored or under-recognized symbolism indigenous to Africa spanning millennia – i.e. the Pyramids of Ancient Egypt and Ancient Nubia.

Materials: Dutch wax print on indigo dye textile (Yoruba Àdìrẹ sourced from Oshogbo, Osun State w/ Chief. Nike Davies Okundaye)

Size: 48 x 30 inches (122 x 76 cm)

Private Collection, New Jersey, USA

*Produced as Artist-In-Residence at the Guest House of Mr. Oliver Enwonwu, Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi, Nigeria.

Oludàmólá: Can you share a pivotal moment in your life or career that significantly influenced your artistic direction?

Àdéjọ́ke: My shift from architecture to art paralleled my ‘coming-out’ process. This was a significant life change about 15 years ago which marked a turning point both in my life and my career. I channeled much energy into the work about sexuality and queer identity from the start, creating drawings, textile works mentioned above and sculptures that reflected a new reality, which I was still learning to be comfortable with as well as growing into. It has been quite a journey! I am so glad I have reached a place of centeredness, grounding and comfort in my mind, body and spirit – a sense of rootedness in my body now that had not been present over a decade ago during the initial phases of ‘coming-out’ as queer. Thus, my artistic direction currently is one where I have successfully traveled the journey towards unity, and thus I can focus on the new journey – duality. As human beings, we all travel a sacred/spiritual path from unity to duality.

Oludàmóla: How do you hope your audience will engage with and interpret the themes of Yoruba culture, queerness, and nature in your art?

Àdéjọ́ke: I hope my audience will see in my work that queerness is a very natural state of being. It is not an ‘altered’ state, and queerness is not about the “flashy” media portrayals of sexual identity. Rather, it is simply a mirror and reflection of the incredible amount of diversity that exists in every aspect of nature. Queer protests are critically about confronting homophobia via a power struggle and the quest for freedom and equality, as with other forms of identity politics. This is important and still needed. However, challenging negative thoughts, the changing of minds, and shifting false mental states are my intellectual preoccupations going forward; for the mind is where it all begins.

For those in my audience who are already queer or allies of queer concerns, I hope my work further inspires and empowers them to keep their bright lights shining. I hope my work encourages them to see their queer identity as sacred, not be tempted to fall victim and become “trapped” in their identity through hyper-sexualized images in the media for example, and to view queerness as naturally as they would to find a flower in the garden or bear witness to the omnipresent Sun.

Medium: Palm spines; Green pastel; Dutch wax textile

Size: 25 x 26 inches (63.5 x 66 cm)

Oludàmólá: How important is it for you to educate others about Yoruba culture through your art, and what methods do you find most effective?

Àdéjọ́ke: Yoruba culture extends back a millennia. We are very old! While I am an innovator, I am also a traditionalist in the sense that Yoruba culture must be “kept alive.” The fact that I can draw inspiration for my work from past references is due to the divine efforts of so many people and institutions over decades, archives preserved over the past century and into the post-colonial sphere – ensuring that Yoruba culture remains valuable, meaningful, powerful and essential. Through my work, I hope to have the same effect on future generations.

Oludàmólá: What upcoming projects or themes are you excited to explore, particularly in the context of Yoruba culture, queer identity, and the integration of art and architecture?

Àdéjọ́ke: I am delighted to share that The Arts Council of African Studies Association’s Triennial Programming Committee has reviewed my presentation Queer Hybridity in Yoruba Art and Architecture on the Panel, Queer Hybrids in Contemporary African Art, and the presentation has been officially accepted to the 19th Triennial Symposium on African Art, which will take place from August 7‒11, 2024, in Chicago, Illinois, USA. The panel is co-chaired by scholars/curators Abigail Celis and Ivy Mills. The Triennial Symposium on African Art holds significant recognition in the research of the arts of Africa and the African Diaspora.

About Àdéjọ́ke Àdéronke Túgbíyélé

Àdéjọ́ke Àdéronke Túgbíyélé hails from the Royal family of former Okin of Igbajo, late Prof. Chief Emmanuel Àkandé Túgbíyélé (Harvard Alum. ‘55, Graduate School of Education); former Vice-Chancellor University of Lagos (UNILAG). Her first group exhibition in Nigeria was at CCALagos – Centre for Contemporary Art Lagos, curated by Bisi Silva and entitled ‘All We Ever Wanted’ in 2011. As a 2013 recipient of the U.S. Student Fulbright Fellowship (USA/Nigeria), she was an Artist-in-Residence at the Guest House of Mr. Oliver Enwonwu – Dolphin Estate, Ikoyi, toured the UNESCO World Heritage Site – Osun Oshogbo Sacred Grove as well as Chief Níke Davis Okúndàyè’s Yoruba Àdìrẹ workshop in Osun State, Nigeria. She is a former Board Member of WHER-Initiative, Abuja, Nigeria and served as US Representative of Solidarity Alliance for Human Rights – Nigeria (2014-2015). Túgbíyélé is co-Juror and mentor with Obodo Nigeria – Queer Artists Fund, a dynamic organization that supports queer artists living and working in Nigeria.

To see more of Túgbíyélé’s work, you can visit her website here.